As discussed in class today, the Civil War–and the role played in it by black Southerners–has recently been the subject of controversy in the national media, thanks to revelations about a faulty claim in a textbook distributed to fourth-graders in Virginia.

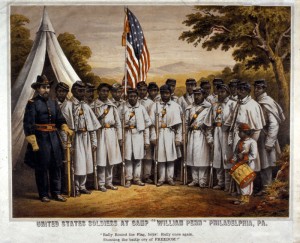

If that article proved one thing, it was that you can’t simply cite as fact everything you read on the Internet–perhaps especially when it’s about the Civil War. But this episode put a national spotlight on the ongoing efforts of Confederate heritage groups like the Sons of Confederate Veterans to argue that thousands of African Americans fought as soldiers for the Confederate army during the Civil War. Academic historians unanimously dispute this claim because it is not supported by documentary evidence, but the claims persist on the Internet and Confederate heritage groups continue to point to historical figures like Weary Clyburn–the man mentioned in the Looking for Lincoln excerpt we watched in class–as proof for broader claims about “black Confederates.” Yet the claims made about Clyburn by Earl Ijames, the historian pictured in that documentary, do not rest on solid evidence. And two historians have even discovered how several Confederate heritage websites falsified the image below to make it look like a picture of black Confederates. You can read about their discovery on the webpage Retouching History.

The authors of the website Retouching History discuss modern falsifications of this image of U.S. Colored Troops.

Later this semester we will talk in greater detail about the reasons why historians dispute the idea of thousands of “black Confederates,” and we’ll read a book by Bruce Levine that deals with the subject. But for now, I’d like you to think about this question: why do some groups like the SCV defend the “black Confederate” thesis so vehemently?

You may have your own speculations about what motivates claims about “black Confederates,” but throughout this semester, you need to be prepared to always defend your claims with evidence. To answer the question of why there are defenders of the “black Confederate” thesis, we need to look closely at what other arguments and hypotheses about the Civil War this idea is typically tied to or advanced with. Only then can we come to some evidence-based conclusions about why finding (or inventing) evidence of black Confederate soldiers matters so much to a small but vocal group of Americans.

Here is your assignment for Blog Post #1. First, read the following articles or blog posts, and be sure to also read through the comments left on them by readers.

- Kevin Levin, “Earl Ijames’s ‘Colored Confederates,'” Civil War Memory blog, May 11, 2009 (scroll through some of the comments too)

- Kevin Levin, “Looking for Silas Chandler,” Civil War Memory blog, March 28, 2010

- “Virginia 4th-grade textbook criticized over claims on black Confederate soldiers,” Washington Post, October 20, 2010 (and comments here)

- “Melvyn Patrick Ely Debates SCV on Fox,” Civil War Memory blog, November 7, 2010 (watch the video)

Then, leave a comment here responding to these questions: What other arguments to defenders of the “black Confederate” thesis make about the Civil War era or the history that has been written about it? Do these other arguments shed any light on the question of why Confederate heritage groups are interested in finding supposed “black Confederates” like Weary Clyburn and Silas Chandler?

Back up your answer to these questions by citing specific quotations, comments, or statements that led you to your conclusion, being sure to say where you found these comments. If another student has already left a comment making the point you wanted to make it, you can still add something new by providing additional supporting evidence in support of it.

Professor McDaniel (Caleb),

So nice to see that my site is being used in this class. I look forward to reading what your students have to say about this controversial and widely misunderstood topic.

In addition to the claim that there were black soldiers fighting on the Confederate side, defenders of the “black Confederate thesis” frequently mention that the Civil War was misrepresented in history and that it not about slavery. For instance, when defending his position in the video, Frank Earnest said the war was not exclusively over slavery but that it also had to do with other issues. Several commentators on the Post article about the textbook also felt Civil War history has been misrepresented and changed to the point where it is no longer reflective of what actually happened, and that in the process, the existence of “black Confederates” has been either dismissed entirely or marginalized. There are many reasons why defenders of the “black Confederate” thesis would want to prove the existence of these people, the chief of which being that it makes their past easier to deal with and understand. Since the average American today would likely judge anyone who said that their family fought on the side of the Confederates or owned slaves—some of the Sons of Confederate Veterans have said their own children or grandchildren will return from school one day convinced they are monsters for fighting on the South’s side—people for whom that is part of their history want to find a way to show that the reality at the time was different from the way it was represented. Even the historian Melvin Patrick Ely has found several instances of blacks and whites doing things in the pre-war South that would surprise most people, and said himself that he would love to be able to find credible instances where blacks were armed and fought on the Confederate side. Nobody wants for their family members to be remembered as monsters, and so they seek out stories of exceptions like Weary Clyburn and Silas Chandler to show that there were ties between blacks and whites that were so close they motivated some blacks to fight on the Confederate side.

If I have internalized anything after reading these blog posts, it is that the scholarship used to support the idea of “Black Confederates” is based on murky assumptions, hearsay, and conjecture. Although, in the defense of Sons of Confederate Veteran (SCV) writers, everyone admits that there is scant evidence to place Africans in the ranks of the Confederate Army. One must resort to assumptions and interpreting (i.e. stretching) the available facts. One main example offered both by SCV writers and Kevin Levin was Weary Clyburn. Proponents of “colored confederates” take the anecdote of Weary Clyburn and expand his story into the generalization that “thousands of them went to war for the Southern States.” ( Earl Ijames’s Colored Confederates) Weary Clyburn is an anecdote, but his anecdote is meant to be a lodestone: a glimpse of the much broader support of the African-American community for the Southern cause.

A second “historical crime” that some bloggers and non-academic historians commit when providing evidence for “colored confederates” is the generalization that presence of a black man in the CSA means that he was a soldier and friend of white soldiers. The 37th Texas account of Silas Chandler assumes that the black Silas and his white master Andrew were friends. It writes that Silas went to war “partially because of their friendship” and partly “he felt that he needed to protect Andrew.” How can they support this? There is no record of Silas Chandler in the Confederate Archives, and because Silas was a slave, he was most likely illiterate (as were most men) and had no journals. They essential made up the story that he was friends with Andrew. It seems to me that it is simply a way to make race relations more politically correct. To keep the façade of political correctness, no distinction within the army is made in the SCV histories. If you were in the army, you were a valiant soldier. It does not include the diaries that tell that blacks were referred to as “boys” and performed menial labor only.

I agree completely with the Washington Post that pro-Confederate sources stretch the truth or jump to conclusions when interpreting history in order to purge themselves of some of the moral and social stigma of being an all-white army trying to preserve the institution of slavery. It is a very big carrot to separate the CSA from the institution of slavery, and I think that all the bloggers we have read imply that it causes the biased reflections on history.

The Fox debate, aside from the squabbles on the numbers or presence of black confederate soldier, nails the reason for this debate. The representative for the SCV said that there is a cover-up to slander the Confederate Army and to make the Civil War only about slavery. The SCV history uses stretched truths in an attempt to portray the Civil War as “the war of Southern Independence” that was caused by many divergences between the North and the South.

When I was in elementary and middle school, I had a vague idea of the Civil War as a clear-cut battle between good and evil, as the North, armed with modern ideals of tolerance and equality, advanced upon the backwards society of the South which had somehow maintained a terrible institution like a tumor in America’s gut. This was the way the story was presented to us, or it was at least given in simple enough terms that this is what I presumed. As I got older, I realized that this was no more reality than Columbus proving wrong an entire society that believed he was going to sail off the edge of the earth. History is much more complex than that, and now I know that the north was infected with racism and that not everyone in the south was a hateful white supremacist.

While the above version of the war may just have been teachers and textbooks putting it in simple enough terms for kids to understand, I feel that popular history is often glossed in such broad absolutes, and that people in general take what they’re given as fact. Take, for instance, people commenting on Levin’s blog about their family stories. Matt McKeon writes:

“When my father retired he decided to research his family background. There was a wonderful story among our uncles and aunts of a long ago jealous wife shooting a rascally husband while he dandled a pretty housemaid on his knee, and then the poor children cheated out of a vast inheritance.

Dad was an old police reporter and dug into the papers and records. The actual story was of poverty, alcoholism and suicide. No murder, no inheritance, not even a housemaid.

The moral of this story: beware of family tradition.”

If it makes a good story, people are likely to hang onto it, and Levin argues that many of the tales of “Black Confederates” have grown out of just such stories with little supporting evidence. While oral history is indeed a source to be respected, when the majority of evidence for a thesis rests on such tales with little else to back it up, we have to question the thesis, especially considering how dramatically history can be revised in a hundred and fifty years. Just look at the reports of Silas Chandler that exist on the internet, which contrast directly with archived historical fact, as pointed out by Levin in his post. Chandler’s ancestor, Ms. Sampson, has sought out the truth. Yet it’s the more glorified version of the similarly-aged boyhood friends going into battle together that was broadcast to a wide audience on the Antiques Roadshow.

While family stories should definitely be considered, if only for the modern mindsets about history that they reveal, ultimately the history worth trusting is that of actual contemporary records.

The point of all this is that the Civil War has already spun into part of an American myth, like a family story except shared by the entire nation, and different regions and people tell it differently, just like different members of a family might tell a story differently to make themselves or their relatives look better or worse, depending on their own opinions or role in the events. The job of historians is to look from an objective perspective, not try to embellish or idealize the facts. The latter is exactly what many Southerners seem to be doing with the Black Confederates idea.

A caveat is that this has happened on both sides; the professor in the Fox video had to point out that the war was not about emancipating slaves from the outset, another flawed view which was put forth in the questionable textbook and which doubtless has originated from the winning team. Ideas such as that of the “Black Confederates” is the way that the losing side is fighting back against what is, admittedly, at times a revisionist history (what Earl Ijames himself, in a retort on Levin’s blog, calls “reconstruction history”). However, they are fighting back by exaggerating sometimes outright twisting the truth, and two wrongs do not make a right.

The SCV representative on the Fox video pointed out, legitimately, that the Civil War was not solely about slavery, but that many complicated factors went into it. However, many of these factors can still be traced back to slavery in some way; for instance, would the question of states’ rights, often pulled out as an alternative cause to the war, have been such a problem if the Southern states had not felt that their right to own slaves was in danger if they remained in the union? Descendants of Confederate soldiers and supporters can’t keep edging away from the fact that their ancestors fought in the defense of slavery in some manner; even if they were fighting for “their homeland,” slavery was a part of their homeland, crucial to its economy and society, that set it apart from the north. Nor can we as American citizens as a whole try to pretend that everyone in the North was a shining abolitionist hero who would gladly sit down and eat dinner with a family of former slaves. The person who truly cares about history needs to study what is known without imposing modern interpretations and wishful thinking on the past.

Arguing that “thousands” of blacks fought for the Confederacy makes the South look really good, as it seriously undermines popular views of them as a barbaric, cruel, racist slaveholding society, if African Americans saw something so good even in a society which accepted the enslavement of their race that they would put their lives on the line to defend it. Or conversely, perhaps they saw something just as bad or even more intimidating in the Union. It’s worth considering that nothing is so clear cut as a Saturday-morning-cartoon-villain view of the South would have us believe. However, the historical details of this argument, such as the number of blacks who actually fought as opposed to just being messengers, cooks, etc., and whether it was by their free will, continues to be fiercely debated, and a solid argument cannot be based on such shaky evidence.

Defenders of the “black confederate” thesis make the argument that record keeping in the Confederate was severely below par relative to today and even the Union’s records. People who commented on some of these articles claimed that even their (white)ancestors have very little record of their service. One reader claimed, “My great-grandfather served two years in the Confederate army, drew a pension after the war (with all the necessary witnesses to his service), but he appears on only one muster roll in that two year period (muster rolls were filled out every two months).” So clearly the record keeping for both black confederates and white confederates is poor and unreliable. Thus, the “black confederate” supporters rely much more heavily on oral history, or stories passed down from their families. “Ms. Sampson does remember hearing quite a bit about Silas. These stories came directly from her grandfather, George, who was Silas’s son.” However, Ms. Sampson chooses not to rely solely on oral history, so she continues to research to discover a more concrete history of her ancestor.

Historians and critics alike claim that the confederate heritage groups try to downplay their reliance on slaves and that slavery was one of the reasons why the war was fought. Confederates claim that the war was fought because of threat of losing their homeland was at stake. I believe they want to find more concrete evidence not only for themselves but also to show the critics. The majority of historians will continue to be skeptical until the defenders of the “black confederate” have a primary source to defend their history. There is no question that the issue of whether or not “black confederates” fought is a murky one and the debate will continue for years. There are always two sides to an issue, and people will ultimately chose to believe what they want to believe.

Defenders of the “black Confederate” thesis argue that the presence of “thousands” of black Southerners in the Confederate armies implies that the role of slavery was very minimal in the South’s decision to leave the Union. However, these groups fail to clarify the role these soldiers had for the Confederacy as most were considered soldier’s slaves as noted by Ken Noe in Levin’s article on Earl Ijames’s “Colored Confederates”. Rather, they list examples of a few men in an attempt to dissuade the notion that the Civil War was fought over slavery. In addition, defenders of the “black Confederate” thesis utilize the role of blacks in the Confederate armies to argue that the South’s decision to secede did not stem from the role of slavery. For example, in the article, titled the “Virginia 4th-grade textbook criticized over claims on black Confederate soldiers,” John Sawyer, chief of staff of the Sons of Confederate Veterans’ Army of Northern Virginia, comments that the war was fought “to preserve their homes and livelihoods”. These groups believe that by listing anecdotes of black Southerners like Weary Clyburn and Silas Chandler who “willingly served” the Confederacy, they will prove that the South did not secede on the basis of slavery; but rather, to maintain their way of life and economic prosperity. Thus, I believe the central component of the “black Confederate” thesis is essentially the role that slavery played in the American Civil War. In Levin’s article about Ijames’s “Colored Confederates,” Sherree Tannen epitomizes these Confederate heritage groups interest in finding “black Confederates” stating, “history is, after all is said and done, a narrative, and everyone wants a respected–and respectful–place in the narrative”. Hence, for Tannen, and I adopt this viewpoint as well, Confederate heritage groups like the Sons of Confederate Veterans are trying minimize the role of slavery in order to make the South’s role in the Civil War appear more sympathetic and attractive. It is much easier for Southerners to take pride in the South’s secession if the Confederacy was formed on the basis of protecting their economic livelihood and distinct way of life. However, it is much more difficult to praise the Confederacy and their drive for “independence” if it was done to protect the institution of slavery. Simply put, Confederate heritage groups are desperate to find blacks who willingly fought for the Confederacy in an attempt to justify the South’s secession as an attempt to protect state’s rights and to downplay the role that slavery played in instigating the Civil War.

Growing up in the South, and in Virginia no less, I can personally share multiple stories about Southerners who will argue that blacks fought in the Civil War, that the Civil War was the “War of Northern Aggression” and that slavery was not near as bad as history books claim. In our specific case of defenders of the “black Confederate” thesis, we see these defenders arguing not only that blacks fought for the Confederacy, but also seeking to show that slavery was not a primary cause of the Civil War. For example, the Chief of Staff of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, John Sawyer, argued in the Washington Post article that the Civil War was “fought to preserve their [Southerner’s] homes and livelihood.” Frank Ernest, member of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, argued that the Civil War was not, in fact, a Civil War, but a war for Southern independence. Because these Sons of Confederate veterans (and others like them) argue that the Civil War was not about slavery, they NEED the “black Confederate” thesis to be true. The “black Confederate” makes their argument legitimate–the Civil War cannot possibly have been about slavery if Southern blacks (who were largely enslaved) fought to defend the Confederacy. Additionally, the “black Confederate” thesis allows the Sons of the Confederate Veterans to argue that their groups are not rooted in racism or hatred, but rather in celebrating the “truth” of their Confederate heritage.

One of the major arguments made by defenders of the “black Confederate” thesis is that Confederate records are so incomplete that the lack of documentation does not prove there were no black soldiers in the Confederate Army. These defenders put great stock in anecdotal and unverified accounts of black Confederates. Commenter John Cummings, on the first blog linked, claims that academic historians intentionally dismiss these anecdotal accounts as unreliable because they have an agenda. In fact, throughout the blogs linked, several comments from defenders basically state that academic historians have an agenda and are actively trying to distort or suppress any evidence of black Confederates because it does not fit with their view of the causes of the Civil War.

This does shed light on why Confederate heritage groups are interested in finding “black Confederates.” Clearly, these groups do not agree with the mainstream views of the causes of the Civil War. They want to emphasize the issues of states’ rights etc. and downplay the role of slavery in causing the War. If they could prove there were black Confederates, then they would be able to justify their claim more effectively that the war wasn’t just about slavery since blacks fought for the South. These heritage groups are presumably proud of their ancestors, so evidence that the South was fighting for something other than slavery is in line with their agenda since slavery is now viewed as inhumane and repugnant.

From the contentious debate about the topic of “black confederates,” it is clear that there is much more at stake than the cold accuracy of Civil War statistics. As a schism from mainstream Civil War scholarship, Confederate heritage groups, like the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV), argue that there were a substantial number of African American soldiers who fought along with white southerners during the Civil War. They argue that, to a great extent, these black soldiers fought because of a strong conviction for Confederate principles and southern conservation. Frank Earnest of the SCV states that it is important to acknowledge the “truth” of this claim in order to award the “black veterans” the honorable distinction of fighting for what they believed in (Fox News). However, it is clear that the SCV is using the possibility of black confederates as a way of downplaying the indignity and horror of slavery in the south.

Despite a significant lack of evidence, the SVC and other similar groups continue to support the claim that blacks fought in significant capacity within the ranks of the Confederate Army. Not only do mainstream history scholars refute the claim of thousands of “black confederates,” but there is no evidence to clarify that there was even one free black soldier in the confederate army. The anecdotal stories about the military service of Silas Chandler and Weary Clayborn are fraught with inaccuracies and missing information. Many of the details of these stories, including the friendly relationships between white and black soldiers and the conviction of southern blacks to confederate principles are unfounded, contrived, and, as Kevin Levin unabashedly states, “Silly.” However, the SVC continues to propagate the idea that blacks fought alongside whites for a mutual cause. People like Earnest speak fondly of the stories of Chandler and Clayborn as historical accounts of black tolerance within the confederacy and black appreciation for confederate values.

Therefore, it is important to ask the question: why is the SCV so intent on a defending a historical interpretation of the Civil War that no respectable scholar is willing to entertain? It is clear that the SCV is not going to great lengths to right the wrongs of history, but is instead trying to find “black confederates” in order to relieve the guilt of hundreds of years of slavery that the Confederacy sought to perpetuate. Although they claim it is their mission to restore the honor of the veteran status of blacks on the confederate side, James McPherson described it most accurately when he stated that “These Confederate heritage groups have been making this claim for years as a way of purging their cause of its association with slavery (Washington Post).”

The defenders of the “black confederates” thesis argue that historians fail to adequately describe the war. The member of the Sons of Confederate Veterans in the video states that the war is labeled as a civil war while in fact it was a war for southern independence. He also says that there are claims that the North went to war because of the issue of slavery and that this is false. (The professor later agrees with him). He feels that (or they feel) that their position and their version of the events is not published and what they believe to be correct is dismissed. The excerpts provided by Kevin Levin in “Looking for Silas Chandler” show that the SCV try to illustrate the relationship between a master and his slave as a positive one full of loyalty and friendship. They claim that the two men were childhood playmates (despite the age difference) and that Silas felt a duty to protect his young master. These arguments do shed light on the reasons behind their push for the propagation of the idea of “black confederates”. It seems that the supporters of this view are interested in emphasizing that slavery was not the reason for the war. If they demonstrate that there were slaves willing to fight for the confederate cause it means that they were trying to preserve their way of life and were interested in breaking away from the United States. It is almost as if they are trying to say that if there were slaves willing to fight for that form of life, then history has depicted life in the south and the institution of slavery in an undeservingly bad light. This idea is further strengthened with the depiction of the relationship between the Chandlers as one of friendship.

It seems to me that one of the main underlying issues underneath this argument about black confederates is the purpose and interpretation of the Civil War in terms of the intentions both sides had. One moment that stuck out in my mind was during the video debate between Frank Ernest and Melvin Patrick Ely, when the idea of political motivation comes up. He tries to say that some historians used to deny black confederate soldiers and are now denying any significant amount. He claims that the idea that the Civil War was mainly about slavery is being defended. There is some truth that a lot of the blame for racism and slavery gets put on the south, definitely more so than the north. It would make sense for the South to try and defend itself by pointing out the existence of black confederate soldiers, whether they are real or even numerous.

The idea of changing the meaning of the war was also seen in the video we watched in class on Tuesday, when a good amount of people often described Abraham Lincoln as a tyrant, and in the video debate when Frank defines the Civil war as the war for southern independence. All of these arguments and statements, plus the existence of black confederates, helps to portray the south in less of a villainous role as the racist slavers. Despite the questionable nature of some of their sources, the veterans seem to cling to the story of black confederates with a very strong voice.

Even if some of the evidence for black confederates is made up or inconsistent, as suggested by some of the blogs of Kevin Levin about the case of Silas, it would make sense for the veterans of the south to try and defend the south this way, suggesting the south wasn’t as racist as it is portrayed by giving black confederates a significant role in history, especially including Stonewall Jackson, as mentioned in the textbook that sparked the debate in the first place.

So despite the questionable sources of these claims that African Americans served in the army, it certainly makes sense why the idea would at least look attractive to historians of the south, and descendants of Confederate soldiers. The main reason for such debate over this idea is that it changes the view of the South during the Civil War; or as some people call it, The War for Southern Independence.

Defenders of the “black Confederate” thesis seem to primarily make two arguments: one, that historians who disagree with the thesis are denying African-Americans the right to honor their ancestors who may have been black Confederates, and two, that historians today place too much focus on slavery as a cause of the Civil War.

The first argument is mostly based on a few examples like Weary Clyburn and Silas Chandler, two supposed black Confederates that groups like the Sons of Confederate Veterans point to as evidence against the typical racist tendencies of their own ancestors. In his article “Earl Ijame’s ‘Colored Confederates’”, Kevin Levin writes of Clyburn and the “difficulties of researching ‘black Confederates’” like him, with Clyburn himself having “no record… in the National Archives”. Yet Ijame maintains that Clyburn and other African-Americans like him served in the Confederate army. The first commenter on this article, John Cummings, scolds Levin for his “barbaric” treatment of a “family memory” and accuses him of demeaning “anyone of color who might embrace an ancestor claiming such fraternization”, to which Levin replies in defense of his position that Ijame had “poor research skills”. This exchange seems to indicate that defenders of the “black Confederate” thesis seem more focused on the emotional aspect of allowing African-Americans to honor their ancestors than the lack of factual evidence to support their claims, even going so far as to ignore the clear evidence against them. Silas Chandler is another example of a supposed black Confederate, made famous by a picture taken of him in uniform with his owner’s son Andrew, with whom he supposedly went to war. In his article “Looking For Silas Chandler”, Levin compares many claims by the 37th Texas website and “numerous SCV websites” to the facts surrounding Silas’s enlistment. For example, claims that Silas and Andrew were “childhood friends” are incongruent with their seven year age difference. Although believers of the “black Confederate” thesis are quick to bring examples like Silas to light, according to Levin even Myra Sampson, a descendent of Silas, agrees that “the story is simply not true”. It is in this same article that Levin points out that “most of the accounts of black Confederate soldiers revolve around a small number of individual names” like Silas and Clyburn, but if even these few examples cannot be proven with absolute facts and records, then what hope does the claim of thousands of black Confederate soldiers have?

The second argument centers on how historians today describe the causes of the Civil War; particularly, defenders of the “black Confederate” thesis claim that these historians should shift their focus away from slavery as a cause in light of the presence of black troops in the Confederate army. The debate between Melvin Patrick Ely and Frank Earnest on Fox News featured in Levin’s article “Melvin Patrick Ely Debates SCV on FOX” features this claim. Earnest, a member of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, posits that “the idea of black Confederates chips away at this myth that the war was over solely slavery and nothing else” and that historians are attempting to “cover up” the idea to maintain slavery as the main cause. However, Ely goes on to point out that, if there really were thousands of black Confederates, then the Confederacy would not have had to debate, halfway through the war, whether or not blacks should be allowed to serve in the army, and at the very least one side of the debate would have used these thousands of troops as an example. Earnest also mentions Louis Steiner as a witness to the service of so many black Confederates, and a commenter on the article, Ed Kennedy, attempts to use Steiner’s records to further support the thesis, but Levin and another commenter, James F. Epperson, point out that that Steiner’s “was not a first-hand account” and that Steiner “did not claim to see black Confederate *soldiers*” explicitly. It is the lack of such clear evidence causes the thesis to remain unsupported.

Both arguments seem to support the idea that organizations like the Sons of Confederate Veterans and other supporters of the “black Confederate” thesis are so interested in finding “examples” like Clyburn and Silas Chandler because it would help to shed a more positive light on their ancestors and the South during the Civil War as a whole. This seems rather ridiculous, however, since historians would have no reason to hide any evidence in support of these claims if there were any. But making these claims and treating them as fact works to benefit these groups, if only so that they can say that their ancestors were not as immoral as some might think they were; by seeking out individuals like Clyburn and Chandler these groups can claim that they honor black Confederates as much as white Confederates, and by supporting the idea that thousands of black Confederates served in the South the groups can attempt to weaken slavery as a primary cause of the Civil War.

Defenders of the “black Confederate” thesis, make many arguments about the Civil War era and its history, including some arguments as to the motivations for the Civil War and the lesser importance of slavery as a factor in the War effort. These arguments, including the argument that the Civil War was not a civil war but instead a war for Southern independence and that slavery was not a major issue in the war, run contrary to most interpretations and show the war in an entirely different light. While these interpretations often come under criticism from historians the likes of Kevin Levin and Melvin Patrick Davis, they are maintained by individuals such as the Sons of Confederate Veterans who stake a significant portion of their cultural identity on such an interpretation. To them, portraying the Confederacy in a different and more forgiving light is more than supporting the losing side, it is standing up for their family honor and heritage.

For these reasons of identity, the defenders the reinterpretation of the Civil War could stand to benefit much from the affirmation of the “black Confederate” thesis. As much of past debate has painted the Confederacy in a rather negative light because of slavery and the oppression of African Americans, the participation and support of part of the African American community would not only provide protections from being seen as a racist organization, but would also legitimize the alternative interpretation in which slavery was not a main component, as African Americans had chosen by themselves to support the Confederacy. For these reasons of clearing their heritage of supposed racism, groups with vested identity in the Confederacy are interested greatly by the finding of such “black Confederates” as Weary Clyburn and Silas Chandler in order to legitimize their claims. Also, despite the considerable attention given to the few found black Confederates, at this point few of these stories can be fully backed up by reputable sources, as existing remaining documents are hard interpret and determine the importance of as shown by the Kevin Levin article “Looking for Silas Chandler”.

History is written by the victors and the Civil War is no exception to this rule. Having grown up in a Northern state, I learned in early American history classes that the Civil War was fought over slavery. However, the argument presented by defenders of the “black Confederate” thesis demonstrate that the causes behind the Civil War were far more complex than simply being over slavery. Members of the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV) hold the war to be a war of Southern Independence and an effort to “to preserve their homes and livelihood.” A commenter on the Washington Post article states that had the war truly been about slavery, the Union would have banned slavery in its states at the beginning of the war. By stating that blacks served as rank and file soldiers of the Confederate military, the war could not have over slavery, an institution which denied blacks of their freedom.

The SCV lists names Weary Clyburn and Silas Chandler as two “black Confederates.” Clyburn is believed to have served in the 12th South Carolina Regiment and Chandler in either the 37th Texas Regiment or the 44th Mississippi Regiment. However, Confederate muster records fail to mention either having mustered out with their regiments. In fact, the SCV’s claims seem hinged around the oral history, something that can be distorted over several generations of telling. While I do agree that Confederate records are less complete then Union ones, I would expect that Confederate regiments would have kept track of who enlisted and when they mustered out into service. As Kevin Levin says in the comments on the Melvin Patrick Ely Debates page, “locate the service records (enlistment papers/muster roll sheets) and you’ve got yourself a black Confederate soldier.”

I am in no way denying the claim that “black Confederates” served in Confederate military, this is supported by firsthand documentation. However, the lack of evidence that men like Weary Clyburn and Silas Chandler served in the Confederate military make the organizations like the SCV appear to be defending their families from the believe that they were racists who fought to defend an institution which denied blacks their freedom. I am sure that there is the potential that hundreds if not thousands of blacks fought for the Confederacy. But until there is evidence proving that these men served in the regiments the SCV claims they have served in, they can be believed as little more than family tales.

Defenders of the Black Confederate’s state that they wish to recognize as many black confederates as possible because “no veteran should go unrecognized.” The spokesperson for the Sons of Confederate Soldiers vehemently defended this position of the organization in the Fox video. While there is no debate on the fact that some confederates were black, the main debate is over the number of blacks who fought. Kevin Levin’s article looking for Silas Chandler works to disprove the acieration that Silas Chandler willingly served in the Confederate Army. It is the position of the defenders of the “black Confederate” thesis that Silas was a solider. I believe that these pro-confederacy supporters have a need to separate themselves from the generally held opinion that all pro-south groups are racists. By recognizing blacks as CSA veterans these groups can separate them from this stigma. Though this is pure supposition. It is apparent in the video that the CSA veteran group spokesperson is very calculating in the statements he says. Because of the behavior of the veteran’s organization member in the video, I believe that his organization is attempting to separate themselves from the stigma of all Pro-Confederate group members are racist.