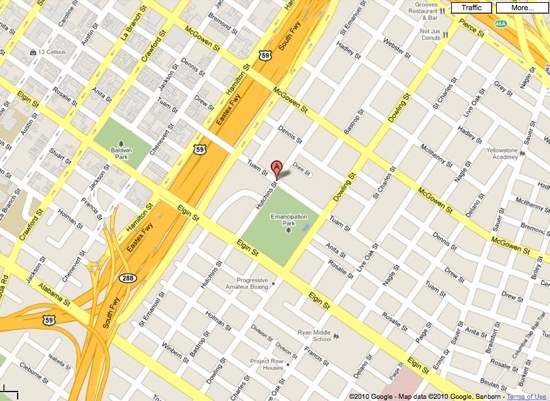

Map of the Microfilm Room in Fondren

Your first library assignment will require you to locate, digitize, and transcribe newspaper or magazine articles about Dick Dowling, the battle of Sabine Pass, and/or the ways they have been remembered and represented over time. The digital items you create as part of this library assignment will eventually be included in the Omeka-based online archive of Dowling materials, so it is especially important to follow the instructions in this prompt carefully. The quality of this archive depends on you.

Here is a step-by-step guide to completing Library Assignment #1.

STEP 1: Go to this Writeboard link and enter the password distributed in class. Now, select one newspaper/magazine issue from List A AND one issue from List B. To claim your issues, click the “Edit This Page” button, and then put your last name in parentheses after the date of your issue. Then, be sure to enter your name in the box at the bottom of the page and click “Save as the Newest Version.” Failing to click this button will erase whatever changes you make and may enable another student to come along later and claim an issue you thought was yours.

STEP 2: Next, go to Fondren library and figure out how to view the two issues you have selected. Most of the Chronicle and Post articles will be available on microfilm in the basement. The Confederate Veteran is available in bound volumes in the Fondren stacks. The other titles should also be available in Fondren; use the catalog to find out where. If you have trouble locating your issues, talk to a reference librarian or email Mercy.

STEP 3: Look through the entire issue you’ve been assigned, and locate any article or item relating to Dowling, Sabine Pass, or the Dowling statue. As you look for articles about Dowling, you should also take some notes about the other kinds of articles and news in this issue of the paper. What else is going on in this issue or around this time? You may wish to look at a couple of issues before and after your assigned issues to get a sense of the context, and you may discover articles that are not specifically about Dowling that you still think are relevant to the sorts of research questions you’ve been asking in your blog posts (about, for example, perceptions of the Confederacy, of slavery and race, or of Irish Americans and Catholics). Save your notes as they may come in handy for Blog Post #6.

STEP 4: Create digital reproductions of the articles you find related to Dowling and Sabine Pass. You should scan the articles as *.TIFF files, using a resolution of 400 DPI. If there is a photograph, use “grayscale.” If there is only text in the article, then “black and white” will suffice. (For help scanning the articles, you can consult librarians in Fondren; they are there to help you!) All of the issues on List A and List B have at least one article about Dowling in them, so you should have at least two *.TIFF files by the end of this step, but you may find other articles you want to digitize because they seem related, and your article may have multiple pages, requiring multiple TIFF files. Give each of your files a brief, unique filename. Check to make sure the file is legible when you open it, and that you can read the words. If zooming in is necessary to read the article, make sure there is not too much pixelation when you zoom in to read. MAKE SURE YOU NOTE THE SECTION AND PAGE NUMBER ON WHICH THE ARTICLE APPEARS.

STEP 5: Transcribe the articles using a word processor. Type out each article word for word in its own document, being careful to avoid typos and indicating in brackets any word you’re unsure of. Save each document using the same filename you used for the image file, but be sure the extension for the file name is different from the image file (e.g., *.doc instead of *.tif).

STEP 6: Finally, log in to OWL-Space and navigate to the tab for HIST 246. You should see a folder called “Dowling Digital Archive Files.” Next to that folder, click on “Add,” and then select “Upload Files.” Now upload both the TIFF image files and the transcription documents you’ve created to the OWL-Space folder.

STEP 7: Now go to this Google form, and for each item you have scanned and transcribed, fill out the information on the form. You will need to fill out the form and press “submit” for each article you have scanned. These fields will provide the metadata for your item, so it is extremely important to fill out the fields as completely and accurately as possible. BE SURE TO PRESS SUBMIT SO YOUR DATA IS NOT LOST. To protect your data, you may want to fill out the answers to the form in a file on your hard drive and then copy and paste them into the form.

All of these steps must be completed by MIDNIGHT on Wednesday, February 23. It is especially important to meet this deadline because your Blog Post #6 will also relate to this assignment, so don’t wait until the last minute. Completing this assignment will require advance planning; technological glitches, library hours, and eleventh-hour problems are not extenuating circumstances that would excuse a failure to meet the deadline. Start soon and you’ll finish happy.

You will receive a grade for this assignment based on your precision and thoroughness in following these instructions, as well as on the thoughtfulness and concision of the brief description you provide about the item when filling out the Google Form. The grade is worth 10% of your total grade.