Yesterday in class, I mentioned that Confederate engineers used 500 slaves to build Fort Griffin–the fortification that proved crucial to Dowling’s victory in the Battle of Sabine Pass. In his book, Sabine Pass, which is still available on Fondren reserve, historian Edward Cotham has this to say about the conditions in which these slaves worked:

Expense records that have survived suggest that most of these slaves were transported from the Houston and Galveston areas to work on this project. This must have been extremely difficult and dangerous work. The records that have survived for similar projects in Galveston reflect a large number of fatalities among the slaves who were brought in and forced to build those fortifications. …

Kellersberg was concerned that the slaves’ owners would not make them available for work if they were abused. As he admitted in one letter requesting additional cornmeal rations in 1861, “They work hard & if such bad policy [underfeeding the slaves] is pursued, we won’t get any more of them.” The fact that the work was difficult, combined with the fact that at times relatively few slaves were available, meant that construction of the new fort at Sabine Pass tended to progress slowly, sometimes crawling to a complete stop. At one point in July, work had been suspended for so long that a local rumor suggested that the plan to build a new fort had been abandoned entirely, to be replaced with a scheme that called for Sabine Pass to be defended by cottonclad steamers alone. …

Most of the important work constructing Fort Griffin seems to have been done in the heat and humidity of August. Nicholas H. Smith, an engineer from Louisiana who had drawn the terrible assignment of supervising on-site all of the finishing touches on the fort, headed his letters from Fort Griffin with the designation “Headquarters of the Army of Mosquitoes,” noting that these insects “are so bad here that it is almost impossible for man or horse to live.” Under these conditions, the tasks of driving pilings, building a palisade, and mounting the remaining guns were proving difficult, if not impossible. Smith’s job was made even harder because of the absence of materials and the scarcity of manpower in what he described as this most “accursed of all places.” Lamenting that Colonel Sulakowski was now forcing him to work approximately eighteen hours out of each twenty-four, Smith summarized his views succinctly: “This place is hell.” Appealing to his supervisor and an even higher authority, Smith wrote near the end of August that “I wish to God you would relieve me of this place.”

(Source: Edward T. Cotham, Jr., Sabine Pass: The Confederacy’s Thermopylae (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2004), 78-79)

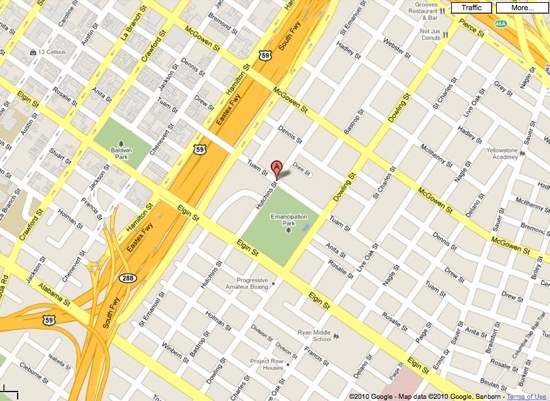

Some questions prompted by this passage: How does the fact that Fort Griffin was built by the forced labor of slaves affect the way you view Dowling and the memory of the battle of Sabine Pass? Should their numbers be included in the numbers of men that Dowling and the Confederates had at their disposal to prepare for the battle? Why do you think that Jefferson Davis and other Dowling promoters did not talk much about the fort itself or the conditions in which it was built? And how should the fort and the battle be remembered today? The official historic park at Sabine Pass mentions briefly the involvement of slaves in construction, but if you were to go to the actual site and see the huge statue of Dowling, what conclusions would you come away with? Is the site–either there or online–organized in such a way to ensure that the role of slavery in the battle and the war is remembered?

Your second blog post assignment is based on the assigned reading for this week. You should read pp. 1-55 of Thomas Brown’s The Public Art of Civil War Commemoration and use specific evidence and examples from that reading when writing your comment. This book is a required text and is available in the Rice University bookstore and on 2-hour reserve at Fondren Library.

Your second blog post assignment is based on the assigned reading for this week. You should read pp. 1-55 of Thomas Brown’s The Public Art of Civil War Commemoration and use specific evidence and examples from that reading when writing your comment. This book is a required text and is available in the Rice University bookstore and on 2-hour reserve at Fondren Library.